History of Food Insecurity:

The Caribbean region has been heavily dependent on expensive food imports for decades. According to the World Bank, 80% to 90% of all food consumed in the Caribbean comes from imports. Only a few countries in the region: Guyana, Belize, and Haiti produced more than 50% of their own food.

The region has traditionally been a raw material producer, with a focus on crops in structural decline (i.e., tobacco and sugar) or simple crops that require little processing (i.e., bananas and sweet potatoes). Exporting unprocessed primary products limits the capture of value in the supply chain, leading to reduced local revenues and fewer job opportunities. It also means that farmers are more exposed to raw commodity prices as they have no differentiated product.

Lingering Impacts from Covid-19 & Ukraine Conflict:

Food inflation in English and Dutch-speaking Caribbean has risen significantly, averaging 10.2% across 20 countries as of March 2022. Food price increases are particularly alarming in Suriname (68.3%), Barbados (19.6%), Jamaica (14.8%), and Guyana (13.4%), making essential purchases unaffordable for many.

Energy prices play a crucial role in the cost of food production and processing. Higher fuel prices can increase the costs of agricultural production, leading to higher prices for produce. Energy is also necessary for food processing, and increased energy prices can contribute to higher household diet costs. Higher fuel prices lead to increased transportation costs, affecting both the cost of importing food and transporting locally produced food to consumer markets. This adds upward pressure on overall food costs, impacting affordability for the population.

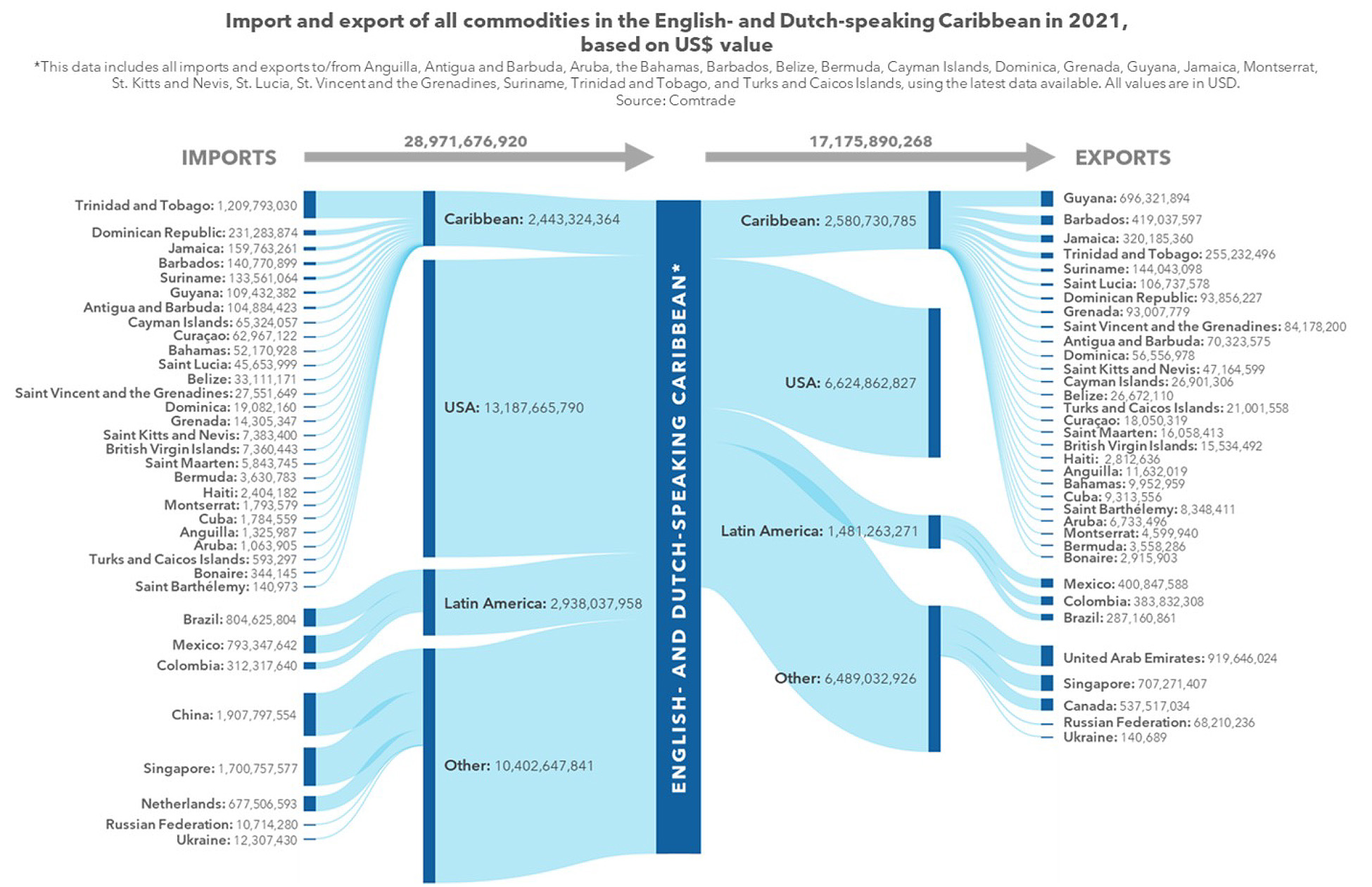

Despite being overall net exporters of fuel, the Caribbean region relies heavily on imports for food imports. The United States, China, and Latin America remain the primary exporters to the region.

Over two years since the declaration of the pandemic, people’s access to markets continues to be impacted in the Caribbean, with 49% of respondents stating that they were unable to access markets in the seven days prior to the August 2022 regional survey. People’s access to markets has gotten worse as compared to April 2020 and is the highest recorded level over the five rounds of regional surveys. Lack of financial means continues to be overwhelmingly reported as the main reason for limited market access, cited by 91% of those who faced a time when they could not access markets in the week prior to the survey.

In just six months, a significant increase has been observed in all three negative strategies to meet food needs. Eight out of ten respondents (83%) indicated that they spent savings to meet their immediate food needs. More than half of respondents (54%) reported to have reduced essential non-food expenditures, such as education and health. Nearly half of respondents (43%) resorted to selling productive assets or goods. All three of these measures may compromise people’s future well-being, resources, and resilience. For instance, the sale of productive assets is likely to affect the sustainability of a household’s livelihoods and may therefore translate into reduced physical and/or economic access to food and essential needs in the medium to long term.

Short-Term Solution:

The proposed shift towards greater vertical integration in the Caribbean agriculture sector, with a focus on value-added crops, processing facilities, and export of finished products, is a strategic response to the challenges outlined in the previous context.

The emphasis on value-added crops and the construction of processing facilities aligns with the goal of increasing the resilience and sustainability of the agriculture sector. Processing facilities can add value to raw agricultural products, create employment opportunities, and contribute to economic diversification. Shifting towards exporting finished products rather than raw materials can lead to higher economic returns. It enhances the competitiveness of Caribbean agricultural products in international markets. International certification of food facilities is crucial for meeting global standards and ensuring the acceptance of Caribbean products in international markets. Cold-chain distribution is essential for preserving the quality and safety of perishable goods during transportation. Investment in cold-chain infrastructure is critical for expanding the reach of Caribbean agricultural products to distant markets. Building human capacity across the agriculture sector is crucial for the successful implementation of vertical integration. Training programs, education, and skill development initiatives are necessary to empower individuals in the industry. Microgrids, powered by renewable energy, will increasingly provide localized and consistent power to island communities and can be strategically positioned next to large industrial customers (such as food processing facilities) but also service dispersed residential communities.

In summary, the proposed shift towards vertical integration, value-addition, and an export-oriented approach in the Caribbean agriculture sector requires a comprehensive strategy that involves infrastructure development, investment in human capital, and sustainable practices. This approach not only addresses the immediate challenges but also positions the region for long-term economic growth and resilience.

New Solution of Financing:

To finance the development of new farms in St. Lucia (due to the significant access to water rights) it would need to be implemented in a quasi-collective approach. The Caribbean food retail industry consists of more than 16K+ stores, of which traditional groceries account for 90%. Large and modern supermarkets and hypermarkets, despite accounting for ~4% of total retail outlets, make up 50%+ of grocery retail sales compared to 28% from traditional grocery retailers/outlets.

This quasi-collective would be via a partnership between investors, local governments, and individual farmers who chose to opt in.

The advantages for the Farmer:

- Access to cheaper financing solutions (compared to traditional private loans)

- Opportunity to sell goods for higher prices

- Education and upskilling required to grow higher value crops

The advantages for the Local Government:

- Promote economic development via food security (less spending on social development programs)

- More political independence from the U.S. and other regional powers by reducing the unequal balance of trade

The advantages for the Investors:

- Reduces the credit and default risk associated with investing in emerging markets

- Meets the UN Sustainability Goal criteria

The advantages for the U.S. Government:

- Reduces the billions of dollars of aid that is annually received by the region (not solving the root problem)

- Reduces the immigration crisis by promoting stability in local economies and creating sustainable economic growth

- Farmers would opt into the collective on a voluntary basis and be able to purchase water rights at the market price. In addition, get financing for equipment. As a member of the collective, they would be mandated to sell a percentage of their produce to the local community and the greater Caribbean region (promote food security). Based on the total produce produced by each farmer on an annual basis they would receive an equity ownership in the collective (equity ownership would be capped to encourage more farmers to join/participate). Farmers would also be entitled to a share of profits made by the collective.

Long-Term Future Financing to Support SMEs:

With all the savings associated with reducing food insecurity and creating more stable income for the region, excess capital can be reinvested into the local economy. To support the next phase of development we need to provide capital to SMEs. Some of the profits from the collective can be used to not only support the farmers but also the local community via partnerships with banks.

We can adopt a successful model from India (Ujjivan) to the Caribbean Market

Joint Liability Group (how to address the creditworthiness problem)

- Issue loans to groups of people rather than individuals

- Formation of the group, participants have every incentive to screen each new entrant so that they do not prove to be a liability (self-screening)

- Once the loan is sanctioned, they are more likely to ensure the amount is used properly

- Shame and guilt associated with being a defaulter in a group will prevent any one person from squandering the money and not repaying the loan

Limit the amount of unsecured loans (how to address the potential default risk)

- Have a hard cap to limit the risk of default and have short tenures

- Charge a higher interest to compensate for risks associated with unsecured lending

- Secured lending can be against equipment and/or property which would reduce the default risk

- Reward groups for paying monthly loans on time by lowering the interest rate or increasing the length of the loan (financial incentive)

Create an inclusive financial leadership program (bi-monthly program)

- Members of the community can talk and share best practices

- Provide basic financial literacy to members who are part of the program

While this solution addresses the individual lack of credit to self-finance a small business it is important to consider the means of disruptions of funds. In the region most customers are underbanked, but many have access to mobile phones. As of Q2 2022 mobile penetration in the Caribbean was at 63.7%. To verify customers, it should be a combination of biometrics (i.e., fingerprint) and mobile phone numbers.

Sources: IICA – Food Security in the Caribbean, World Food Program – Caribbean Food Security & Livelihoods Survey and Ookla